Over the last couple of years there’s been a lot of focus on legislation concerning internet privacy and regulation. SOPA came and went. CISPA was effectively (so we thought at the time) dead but is rearing its ugly head once again. ACTA was killed last summer. But all of those can have thousands of words dedicated to just them on their own. Today we’re going to be talking about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, affectionately known as CFAA for short.

Over the last couple of years there’s been a lot of focus on legislation concerning internet privacy and regulation. SOPA came and went. CISPA was effectively (so we thought at the time) dead but is rearing its ugly head once again. ACTA was killed last summer. But all of those can have thousands of words dedicated to just them on their own. Today we’re going to be talking about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, affectionately known as CFAA for short.

The CFAA

The goal of the CFAA (when it was born from from the twisting nether ironically in 1984) was to reduce unauthorized access to computer systems for government and financial institutions. OK, fair enough. But the number of amendments that were attached to it over the next couple of decades changed its tone. In 1994 Congress turned it into a weapon for private litigants suing for civil damages, giving private business a means to sue employees for alleged information theft. 2001’s Patriot Act amended it to allow searching records from a user’s ISP. Each amendment suffers the same kind of vague, broad and overreaching language that we’ve grown to know and cringe at just like other proposed internet regulation has. A broad interpretation of the CFAA justified criminal charges for employees that violated a company’s acceptable use policy or violating an internet terms of use policy. Criminalized. Thankfully that last one was changed again in 2011, to bring the focus of the law back to what it originally was – combating unauthorized access to information. But it still had the power to destroy.

The case of Aaron Swartz

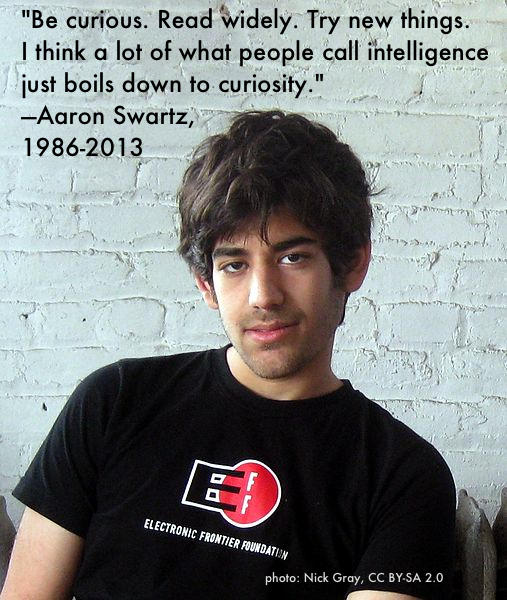

The most prominent case illustrating this was that of Aaron Swartz, a bright digital innovator and activist that helped develop RSS content syndication and the creation of the Creative Commons licenses. He also was the founder of the online group Demand Progress, an activist group that was well known for their digital campaign against SOPA. The case was around his access to information from JSTOR, a not-for-profit repository of scholarly and academic journals created in 1995 to help academic libraries and publishers provide access to their works without taking up physical shelf space. Users that have JSTOR accounts through an academic institution have free and unfettered access to this repository. Swartz’s position as a research fellow at Harvard University granted him access to the JSTOR system. According to the Department of Justice however, Swartz did so from a “protected computer” on MIT’s campus, with the intention of stealing documents and sharing them sharing them over numerous file-sharing sites, leaving him open to prosecution with the full strength of the CFAA. If he was convicted of the charges (wire fraud and computer fraud as violations of the CFAA) he could have faced up to 35 years in prison and fines up to $1 million. Sadly, Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment this past January.

The most prominent case illustrating this was that of Aaron Swartz, a bright digital innovator and activist that helped develop RSS content syndication and the creation of the Creative Commons licenses. He also was the founder of the online group Demand Progress, an activist group that was well known for their digital campaign against SOPA. The case was around his access to information from JSTOR, a not-for-profit repository of scholarly and academic journals created in 1995 to help academic libraries and publishers provide access to their works without taking up physical shelf space. Users that have JSTOR accounts through an academic institution have free and unfettered access to this repository. Swartz’s position as a research fellow at Harvard University granted him access to the JSTOR system. According to the Department of Justice however, Swartz did so from a “protected computer” on MIT’s campus, with the intention of stealing documents and sharing them sharing them over numerous file-sharing sites, leaving him open to prosecution with the full strength of the CFAA. If he was convicted of the charges (wire fraud and computer fraud as violations of the CFAA) he could have faced up to 35 years in prison and fines up to $1 million. Sadly, Swartz hanged himself in his Brooklyn apartment this past January.

There are tons more details to this case I’m glossing over, but you can read more about the whole thing at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Present Power and Proposed Changes

That’s the power the CFAA has as it stands. In the wake of Aaron Swartz’s death, many politicians, including SOPA critics Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) and Rep. Jared Polis (D-CO), raised questions about how the government handled the case, and Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) proposed to reform the CFAA with Aaron’s Law, to prevent what happened to Swartz to happen to other computer users. This reform is extremely important in the internet age, because according to the bill, you don’t have to be a hacker or know anything about hacking to be charged for unauthorized access. In the words of Orin Kerr, a law professor at George Washington University,

“Breaching an agreement or ignoring your boss might be bad. But should it be a federal crime just because it involves a computer? If interpreted this way, the law gives computer owners the power to criminalize any computer use they don’t like. Imagine the Republican Party setting up a public website and announcing that no Democrats can visit. Every Democrat who checked out the site could be a criminal for exceeding authorized access.”

So reforming this bill would be in the best interests of the internet and all American internet users, right? So why are new proposed amendments aimed at dealing more damage instead of fixing what’s broken? Looking at the new draft (which you can see here) just talking about violating the CFAA will carry the same punishment as actually completing the act itself, by adding the short phrase “for the completed offense.” There’s also language that links CFAA violations to racketeering, putting every violator on the same level as a member of an criminal organization. In addition to violating website’s fine print being a criminal act, the proposed changes expand the scope of civil seizure and forfeiture by the federal government. And one of the most frightening additions is a section on “exceeding authorized use,” meaning that if I want to access information I legally have access for an “impermissible purpose” then I’m punishable. I’m not saying that’s a common thing, but it could be another arrow in a prosecutor’s quiver.

Terms of Use Violations and… Seventeen Magazine?

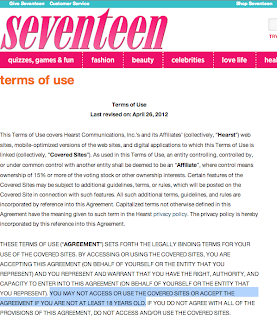

Yes, that’s right, Seventeen Magazine. Upon hearing of the new proposed earlier this month, they immediately changed a very specific part of their terms of service. Their terms of service used to read that you had to be at least 18 years of age to access the website, meaning that if you couldn’t access Seventeen if you were… actually 17. They have a readership of 4.5 million teenage readers, whose average age is 16 and a half. As of April 3rd, that language has been removed. Otherwise, under the new proposed CFAA changes, over 4 million teenagers could have been charged with computer crimes just for visiting the site, violating the user site agreement fine print. Hearst Magazines realized that this was ridiculous, and thankfully chose not to turn an army of teenagers into felons.

Yes, that’s right, Seventeen Magazine. Upon hearing of the new proposed earlier this month, they immediately changed a very specific part of their terms of service. Their terms of service used to read that you had to be at least 18 years of age to access the website, meaning that if you couldn’t access Seventeen if you were… actually 17. They have a readership of 4.5 million teenage readers, whose average age is 16 and a half. As of April 3rd, that language has been removed. Otherwise, under the new proposed CFAA changes, over 4 million teenagers could have been charged with computer crimes just for visiting the site, violating the user site agreement fine print. Hearst Magazines realized that this was ridiculous, and thankfully chose not to turn an army of teenagers into felons.

It’s important that people know what’s going on with this kind of legislation – any laws that affect computer use affect all of us, and we as citizens should actively be making sure that our own day-to-day activity can’t be potentially weaponized against us. If you want to contact your representatives about the CFAA (or anything else for that matter) the EFF has a lookup tool you can use to know where to send your comments and letters.

This is far from the first and far from the last when it comes to skewed computer law. Outside of recruiting more geeks in Congress, our voice is all we have.