Virtual worlds can become virtual laboratories. Put a bunch of people together and allow them to behave as they want within a given set of rules, and the data that can be extracted from it can be highly valuable. Look at our global health crisis right now and it may be tough to see how this can apply. But studying behaviors in crisis is something that could be done in say oh I don’t know, an MMO with a large player base in safe and sometimes accidental way.

And now that accidental research is being used in the fight against the spread of COVID-19. So what am I talking about?

In 2005, World of Warcraft experienced what could only be called the strangest thing seen in the realms of Azeroth. An accidental event known as the Corrupted Blood Incident involved a simple debuff spreading globally killing our virtual avatars without quarter, and without intention. It started with the introduction of the Zul’Gurub raid instance, and its final boss Hakkar the Soulflayer. Hakkar, a scourge to healers everywhere, would pop raid members with Corrupted Blood, a debuff that would cause fast damage over time and quickly kill players if the healers dropped the ball even a little. Stuff like this is generally isolated to the boss encounter, and after it’s over the raid party can leave and go about their business, hopefully with some new shiny loot. However, there were a couple of overlooked mechanics that caused some issues:

In 2005, World of Warcraft experienced what could only be called the strangest thing seen in the realms of Azeroth. An accidental event known as the Corrupted Blood Incident involved a simple debuff spreading globally killing our virtual avatars without quarter, and without intention. It started with the introduction of the Zul’Gurub raid instance, and its final boss Hakkar the Soulflayer. Hakkar, a scourge to healers everywhere, would pop raid members with Corrupted Blood, a debuff that would cause fast damage over time and quickly kill players if the healers dropped the ball even a little. Stuff like this is generally isolated to the boss encounter, and after it’s over the raid party can leave and go about their business, hopefully with some new shiny loot. However, there were a couple of overlooked mechanics that caused some issues:

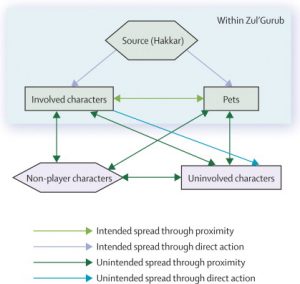

- Hunters and warlock classes, who generally have a pet active as part of their damage dealing, could dismiss their pets. Upon leaving the raid, and long after the debuff was gone, those pets retained the debuff after being re-summoned.

- Corrupted blood didn’t only affect the character that was directly attacked, but was infectious and could jump to nearby players and NPC’s within a 100 yard radius.

- NPC’s that were infected did not die from carrying the debuff. They continued their loops as active disease carriers.

These three points caused the major source of the spread. Non-player-characters had now become asymptomatic infection vectors. And in major cities with high player density, this more or less led to walking into the city and dropping dead. Granted, “dying” in World of Warcraft is temporary and the player is quickly resurrected afterwards by various means, but it was still an interesting study in how disease spreads, if not just an outright nuisance. Major cities were strewn with skeletons for days, massively disrupting gameplay and game operations in general. You can even take a look at videos players posted on YouTube to see the devastation.

These three points caused the major source of the spread. Non-player-characters had now become asymptomatic infection vectors. And in major cities with high player density, this more or less led to walking into the city and dropping dead. Granted, “dying” in World of Warcraft is temporary and the player is quickly resurrected afterwards by various means, but it was still an interesting study in how disease spreads, if not just an outright nuisance. Major cities were strewn with skeletons for days, massively disrupting gameplay and game operations in general. You can even take a look at videos players posted on YouTube to see the devastation.

Blizzard tried to put a voluntary quarantine in place to curtail the spread of the debuff, but as we can all probably tell while living through our current situation, many players reacted in many different ways. Unsurprisingly, not a lot of people took the quarantine request from Blizzard seriously. Some did listen and just logged off, effectively taking their player out of the game (self quarantine). We saw some flee major cities and stay in the countryside and sparse areas with low numbers of NPC’s (social distancing). Some folks were helpful, for example warning people on the outskirts of Goldshire not to head into Stormwind. Even healer classes were volunteering to remove the debuff from affected players and risk getting it themselves (like our front line medical workers). And then there of course there were the trolls, who took advantage of the situation to spread the seeds of chaos and actively spread the debuff further to grief other players. After many hard restarts, Blizzard fixed the issue to restrict Corrupted Blood to be unable to exist outside of the confines of the Zul’Gurub raid.

This wouldn’t be the only outbreak in Blizzard’s virtual worlds. Those accidental scientists used the data to model the Great Zombie Plague in 2008 as part of their Wrath of the Lich King expansion, configuring it so that the plague wasn’t 100% communicable to nearby players and characters, and was more in line with a “true to life” outbreak.

In 2007, two years after the Corrupted Blood Incident, Dr. Eric Lofgren and Dr. Nina Fefferman analyzed the event and authored a paper entitled “The untapped potential of virtual game worlds to shed light on real world epidemics” that goes into the science of the spread of disease through both direct action and proximity. The paper highlights the parallels between real and virtual worlds, and they talk about them in a bit more detail in a recent interview with PC Gamer. “For me, it was a good illustration of how important it is to understand people’s behaviors,” he says in the PC Gamer interview. “When people react to public health emergencies, how those reactions really shape the course of things. We often view epidemics as these things that sort of happen to people. There’s a virus and it’s doing things. But really it’s a virus that’s spreading between people, and how people interact and behave and comply with authority figures, or don’t, those are all very important things. And also that these things are very chaotic. You can’t really predict ‘oh yeah, everyone will quarantine. It’ll be fine.’ No, they won’t.”

In 2007, two years after the Corrupted Blood Incident, Dr. Eric Lofgren and Dr. Nina Fefferman analyzed the event and authored a paper entitled “The untapped potential of virtual game worlds to shed light on real world epidemics” that goes into the science of the spread of disease through both direct action and proximity. The paper highlights the parallels between real and virtual worlds, and they talk about them in a bit more detail in a recent interview with PC Gamer. “For me, it was a good illustration of how important it is to understand people’s behaviors,” he says in the PC Gamer interview. “When people react to public health emergencies, how those reactions really shape the course of things. We often view epidemics as these things that sort of happen to people. There’s a virus and it’s doing things. But really it’s a virus that’s spreading between people, and how people interact and behave and comply with authority figures, or don’t, those are all very important things. And also that these things are very chaotic. You can’t really predict ‘oh yeah, everyone will quarantine. It’ll be fine.’ No, they won’t.”

“It led me to think really deeply about how people perceive threats and how differences in that perception can change how they behave,” Dr. Fefferman writes. “A lot of my work since then has been in trying to build models of the social construction of risk perception and I don’t think I would have come to that as easily if I hadn’t spent time thinking about the discussions WoW players had in real time about Corrupted Blood and how to act in the game based on the understanding they built from those discussions.”

The call for social distancing and self-quarantines are the same in the virtual world as they are in ours. Ignoring those pleas from officials and medical experts, while not intentionally trying to cause harm to others, is still wildly dangerous and needs to be curbed. Dr. Lofgren had some critics who said that players trying to grief others through intentional infection has no real analog in the real world. He begs to differ, so I leave you with the most important takeaway:

“People aren’t intentionally getting people sick. And they might not be intentionally getting people sick, but wilfully ignoring your potential to get people sick is pretty close to that. You start to see people like ‘oh this isn’t a big deal, I’m not going to change my behavior. I’m going to the concert and then going to see my elderly grandma anyway.’ Maybe don’t do that. That’s a big takeaway. Epidemics are a social problem… Minimizing the seriousness of something is sort of real-world griefing.”

You can check out the full interview with PC Gamer here.